PK grew up in Hickory, North Carolina. His life came to be centered around Auburn, but he was always a Carolina boy at heart.

He attended Hickory public schools—Viewmont Elementary, College Park Junior High—from 1960-1969. In the fall of 1969 he joined his cousins Bryan and Rusty at Sewanee Military Academy in Sewanee, Tennessee. The military program was dropped after his junior year so he graduated from Sewanee Academy in the first post-military graduating class in 1972. During his senior year at Sewanee, PK was the third highest-ranking student.

PK had the size and talent to play football, but it wasn’t his thing and he didn’t enjoy it. So in a life-defining move, he joined the swim team. Cousin Rusty says: “Our swim team—I was on it too—had always had a couple of guys that were really good, but we weren’t much of a threat in a large meet. That changed when PK joined the team.” The team already had some outstanding divers, but PK was so talented in so many freestyle events the team became a force to be reckoned with. Rusty adds: “It seemed to do all kind of things for him. He walked taller, became a big man on campus, and was just generally happier, it seemed. He was a different guy after that first season.”

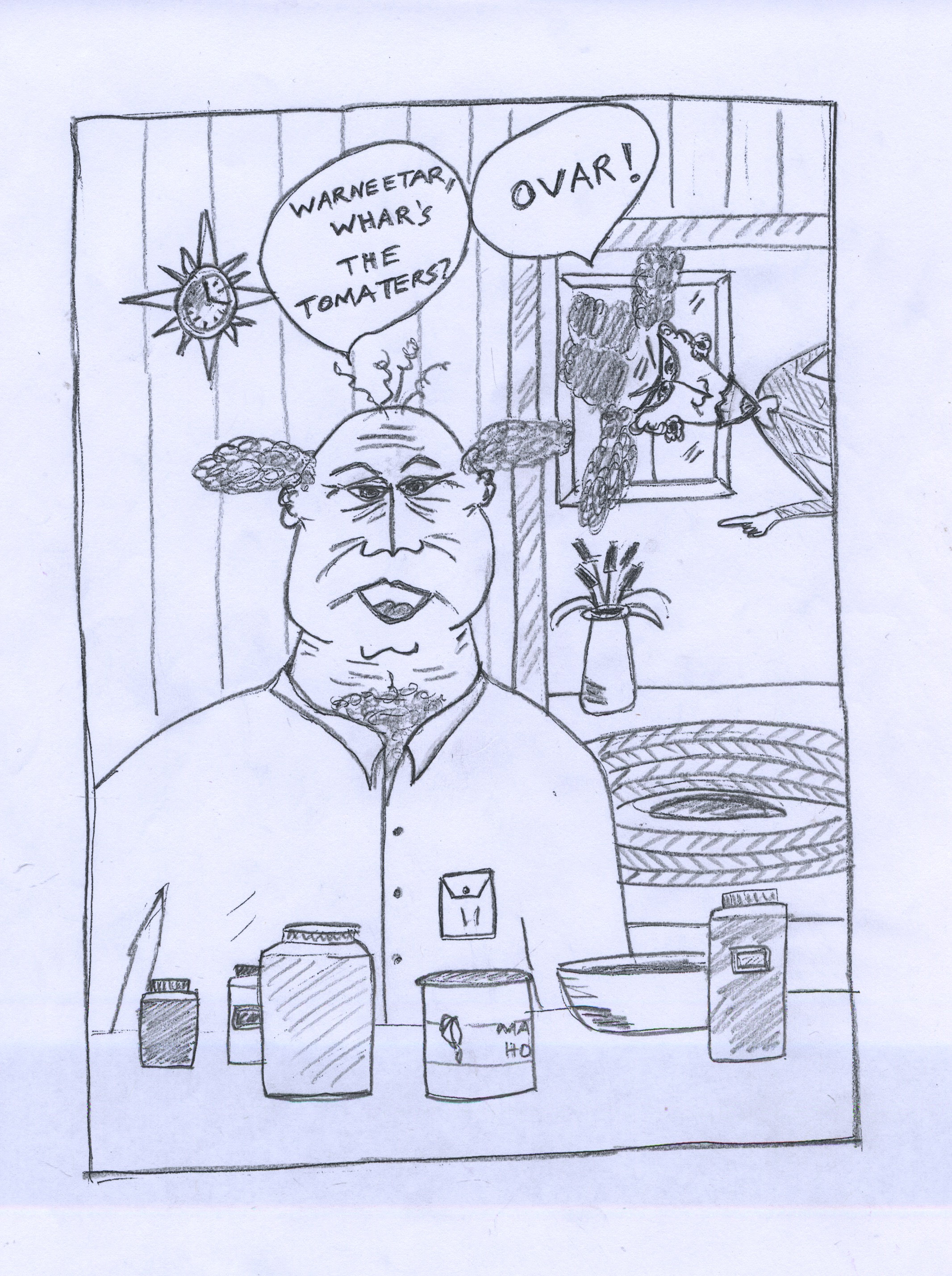

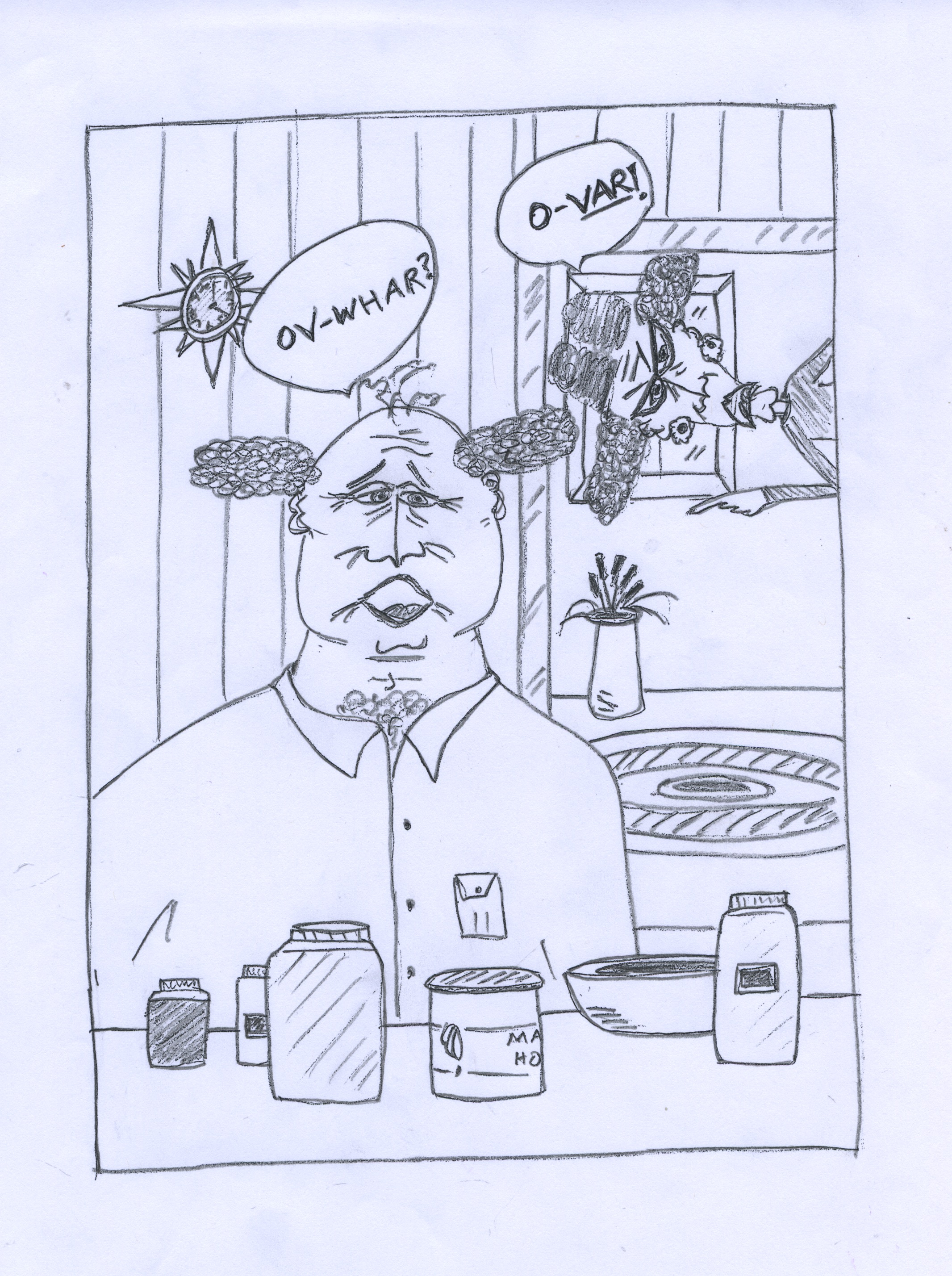

Of course Margaret Carol—“Sis”—was a constant presence in his life. Their parents divorced in 1958, and PK and MC stayed in Hickory with their mother, while their father moved to Asheville. PK and MC experienced the usual sibling warfare when they were young. They later laughed about the time PK chased MC through the house with a hammer, and MC just made it into her room and locked the door in time. About 1960, MC and PK were attending separate summer camps, and at a social arranged for the boys at Camp Rockmont, and the girls at Camp Merrimac, to meet, PK confided in MC that he was homesick. “That night I cried myself to sleep worrying about him,” MC says. MC also remembers coming home from the hospital with her newborn daughter Molly in 1986, and PK was the first person there. Molly always had a special place in PK’s heart. As Sis and PK grew up, over the years they grew closer. When their mother died in 1978, their relationship became stronger than ever.

PK, always a dog lover, had a veterinary career as well as a swimming career in mind when he came to Auburn in 1972. It was either then, or when he had left for Sewanee (MC can’t remember which), that MC told him this was his chance to become “Paul.” PK would have none of it. I don’t remember asking, but I recall PK once confiding in me what both the “P” and the “K” stood for, and asked me to keep it to myself. Though I hardly think it’s a classified secret, I’ve always honored that. At Auburn he became a walk-on member of the swim team during Coach Eddie Reese’s first season as the Auburn head coach. As teammate John Asmuth says, “PK was one of the most phenomenal success stories in college swimming history as he improved from 1:58 in the 200 yard freestyle to 1:39.” In March 1974, PK and sophomore teammates Mike Drews, Logan Pierson, and John Pierson became Auburn’s first swimming All-Americans as members of the 800 yard freestyle relay. The next year he was named an individual All-American following his fourth-place finish in the 200-yard freestyle at the NCAA championships. At the end of his collegiate career, he was a six-time All-American, the school record holder in the 200-yard freestyle, and had been voted one of the team’s captains in his junior and senior years.

Those were glory years for PK. In a hometown newspaper article in 1975, PK said, “I’m what you call a late bloomer for swimming . . . Most people who are going to be good in swimming start to show good times early. I was really slow in high school. I decided to go to Auburn because they had hired a new coach and he had gotten some really good swimmers. I didn’t want to be in the outside lane again so I had to work hard. My first year in college my times weren’t too good but last year I really started to improve. Last year I was an All-American at Auburn. The reason my times have improved so much is because I stopped being a four month a year man and started swimming all the time.”

In summers PK began swimming ten miles a day. During the school year he would be in the pool from 6:30-8:30 am, then go to class, then to the weight room, then back in the pool from 4:30-6:30. He went from a walk-on freshman to a half-time scholarship as a sophomore, to a full ride in his junior and senior years.

In 1975 PK was in California training for the 1976 Olympics. His speeds were losing some of their edge, and as ill fortune would have it, he contracted mononucleosis. Sadly, team member Mike Drews broke his ankle around the same time, further crippling the team. Mark Spitz beat out PK for his spot on the U.S. team. Anybody who knew PK knows how that disappointment haunted him.

When PK came to Auburn he became a member of the Beta Theta Pi fraternity, and his roommate was Howard King. They became lifelong friends, and I can attest to the depth of that bond in PK’s life. After I got to know Howard, it was easy to understand why.

PK graduated from Auburn in 1976, and that August he and Patria Fitzpatrick married and lived in Gold Hill, outside Auburn, as PK became a student coaching assistant with the 1977 Auburn swim team. Eddie Reese had gone to the University of Texas and Richard Quick was the new coach. Among other accomplishments in that era, PK, and Patria, were involved in the recruiting of legendary Auburn swimmer Rowdy Gaines.

PK and Patria lived in a beautiful 1832 house owned by George Robertson. That’s when PK got to know George’s son, Pooka, who became a lifelong friend and neighbor. Pooka died in 2019. Mr. Robertson was renting the recently renovated and relocated house for the first time, so the young couple had to interview as potential tenants. In a fortunate twist of fate, when they arrived for the interview one of Mr. George’s hackney show ponies had attempted to jump over a gate and gotten caught atop it. Patria, an equestrian, and PK, an athlete, managed to free the pony with no injuries. Interview over. They became close friends with Mr. George, who allowed them to keep two horses in his pasture. Patria remembers PK coming home and catching his favorite, Dude, a large dun Quarter Horse, and riding him bareback. In 1979, they moved to Elon College, North Carolina where PK became head coach for a swim club. In 1982, PK and Patria divorced and PK came back to Auburn that year to pursue an MBA degree and to serve as an assistant swim coach again under Coach Richard Quick from 1982-1985. PK finished the coursework for the MBA, but having developed serious doubts about the sedentary life of a businessman, never completed the final project.

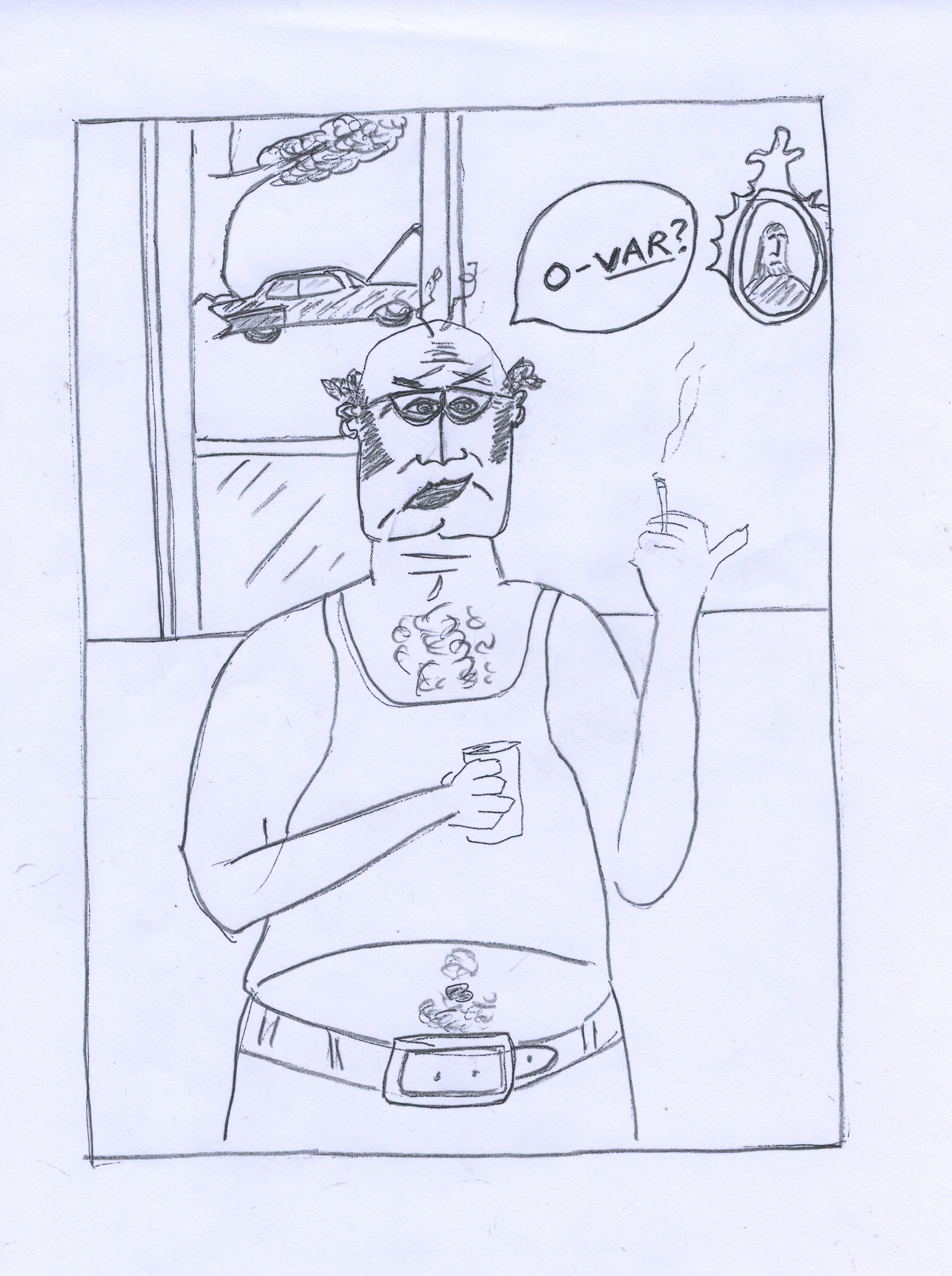

In 1982, PK moved into a hunting cabin with a huge fireplace in rural Chambers county owned by Dr. Allen Edgar. Patria and I had been in graduate school together at Auburn in the seventies, and I had met PK then, but these were the years when I really got to know him. We frequented Rusty’s, famed for oysters and fried chicken. Sandy Langner, recently divorced from Auburn legend David Langner, became a waitress at Rusty’s in 1985, and she and PK had their first date on Groundhog Day, 1986. In August Sandy moved out to the cabin. I can remember get-togethers at the cabin when it felt like a hundred people, including many Auburn athletes, were there. PK was an early fan of Jimmy Buffett, who rightly bragged that he could always “draw a crowd,” and you could say the same thing for PK. He was a people magnet. Those years, up until the razing of the famed Auburn waterhole in the early 2000’s, were the heyday of Harry’s Bar, owned by Maurice “Mo” Weeks, where for years PK was a regular, and got to know many of the denizens of Auburn’s demimonde. It seemed PK knew everybody.

During that period, I owned and ran a small printing business in Auburn and stayed very busy, but I found time to play in the Auburn city softball league, on Brian Upright’s Pet Stop team. PK was one of three left-handed sluggers on that team. Another was Dave Marsh, a fellow Auburn swimmer and later coach. Those lefties loved that field by the old Auburn city pool with its short right field fence. We won the league in 1983.

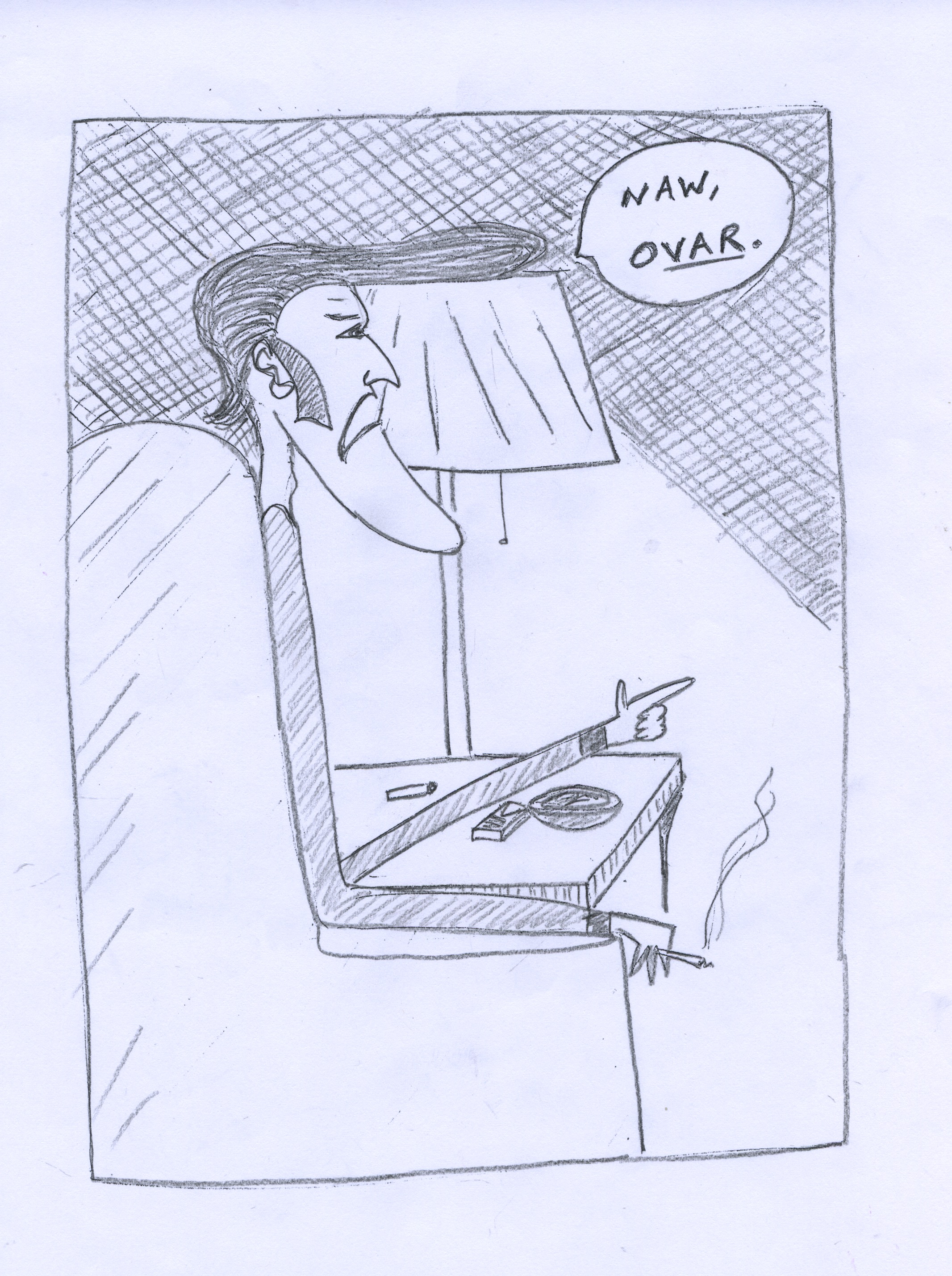

On Halloween 1987 I went out to a party at the cabin. Some folks had come in costume, including Sandy and PK as a bride and groom, and John Burrows as a preacher. It turned out he was a preacher, and Sandy and PK were a bride and groom. The wedding took place amid the revelry.

Not long after that, PK and Sandy bought the cabin and five acres from Dr. Edgar. In 1991, Sandy’s twelve year old son Brad Langner came to live with them, and PK, a master builder, began the transformation (“renovation” isn’t enough word) of the cabin into the stunning and unique wonder it became. First he added a bedroom and bathroom, then around 1995 he tore off the front of the house and built the great room and kitchen, and sometime later added the back deck. There would be no way to count the parties, meals, football games (with limoncello, store-bought, later homemade), New Years celebrations, and many other gatherings at that beautiful place. The most memorable gatherings, for me, were the annual Yard Games which PK and Sandy hosted for twenty-five years (1988-2013). For many years PK set up a huge grill in the back yard where he greasied himself barbecuing chicken halves. Eventually he wearied of that chore and it became a total, instead of partial, covered dish affair. Yard Games was always the first Saturday in May, same as the Kentucky Derby, and for a quarter century that date was a red letter day on the calendar, a rite of passage into spring and summer. The day always meant a lot to me personally since my son Martin’s birthday is May 3: every now and then the days would coincide, and if they didn’t, they were close. We always had a cake for Martin, the candles counting up as the years counted down. In the early days the crowds were teeming and we played volleyball, croquet, bocci, badminton, horseshoes, and shot the potato gun. I don’t think the sport of “washers” was in the picture yet. The weather was almost always gorgeous in the way only early May in the south can be, but I do remember a very rainy Yard Games that I’m sure Martin and Frank Smith remember too.

During the eighties PK started the tradition of canoe trips on the Tallapoosa River. Typically we, a flotilla of three or four canoes, would put in at Bibby’s Ferry, just downstream from the spot they would own years later, and would get out the next day, sunburned, at Horseshoe Bend, with a night around a campfire at the edge of somebody’s pasture in between. I remember one night, after we’d finally made it to our tents, when a Chuck-will’s-widow landed in the campsite and called, very loudly, all night to his love interest upstream. I remember another trip I couldn’t go on, in October of 1984. Auburn was playing Florida State that Saturday night. We were listening to the game at Doc Markle’s cabin in Auburn, not knowing that the guys on the trip had miraculously gotten a radio signal and were listening to it too—a thriller in Tallahassee that came down to the last minute, with Auburn winning 42-41. We compared notes later. Those float trips restored the soul. But I have to admit, there were some long slow stretches on the river, and I remember the year we equipped the canoes with troll motors. We never said we were trying to be heroes.

In 2010, PK and Sandy, Brad, Darren Medford, and Phil Thompson bought their beautiful site on a high bank overlooking the Tallapoosa, just above Bibby’s Ferry and across the river from Frog Eye, with the Shoals a short jaunt upstream. They moved a doll’s house from Brad and his wife Laura’s back yard up there in 2011, and in 2012 PK started work on what was to become another unique and wondrous creation, the River House. For the last several years we enjoyed float trips, restorative afternoons at the Shoals, good food, and good friends. One afternoon in 2017, PK was sitting in his chair in the shallow water of the Shoals, and as he often did, reached down and raked his hand through the sand and rocks, and picked up a rock. On that particular afternoon it was no ordinary rock, but a stunning, perfectly preserved three-inch long spearhead. On another afternoon at the Shoals, my dachshund Bernard, miraculous survivor of a number of near-death experiences, had yet another when he made the mistake of trying to swim out to the rocks where I was enjoying the rush of the cool water, and got caught in the current. As he spun around and bobbed under, PK leapt to the rescue. He snared him in the water plants on the opposite bank. Just in time. Bernard got PK a bottle of his favorite whiskey.

In 2016, Brad and Laura gave the world the miniature force of nature called Ruby June. I guess Brad and Laura are Daddy and Mommy, but Sandy became Milly, and PK, Chief. There’s a photograph of June and Chief, back to back on the sofa reading, that says it all.

No account of PK’s life would be complete without a mention of his dogs. There were the exceptions—Jessie and Bessie, the pointers, Dottie, the German Shorthair Pointer, Buddy the irascible dachshund PK and Sandy got from Mo Weeks, who liked Sandy, tolerated PK, and bit everybody else—but PK’s breed of choice, as everybody knows, was Chesapeake Bay Retrievers, and he had a long line of them, dating to his first, Tawn, later known as Granny. Granny was a smarty, who legend has it could differentiate between the words “ball” and “bowl,” and fetch the one you asked for. I’ll probably leave somebody out, but after Granny came Folly. Actually, there were two Follys, the first stolen from PK’s and Patria’s back yard as a puppy, the second her replacement, whom he had when he met Sandy. Then there were Bailey, Susie, Annabelle, and the wonderful Peggy who, along with Dottie, survives him. (Note: since I first wrote this, we lost Peggy. She was a wonderful dog.)

PK loved those dogs, he loved people, he loved music, reading, and good times. He hated the poisoned politics of our divided times. If you needed help, he was there. He was a generous, loving, talented, unforgettable man who left a deep mark on everyone he touched.

Somehow I, all of us, need to keep going from this point, but it won’t ever be the same.

April 5, 2020

Return to Index